Illusionism is the Conservative Position

No other view can accommodate two essential intuitions

Ever since bravely coming out as an illusionist, I’ve been meaning to set aside some time for writing a more substantial piece where I lay out exactly what convinced me and tackle all the most powerful objections. But whenever I sit down to actually start putting that second half together, I always find myself getting stuck. At least online, a sizeable chunk of people who reject illusionism aren’t doing so because any particular argument convinced them it was false — instead, they’re just automatically dismissing it as too extreme, counterintuitive, or downright crazy to be worth considering in the first place. (See Galen Strawson’s embarrassingly bad essay from a few years ago if you want a good example of this incredulous-stare-as-critique approach.)

It should come as no surprise to hear that I find this style of engagement obnoxious, and that I would find it obnoxious even if the critics were right to see illusionism as some wild, out-there idea — plenty of wild, out-there ideas have turned out to be true! But what makes the knee-jerk dismissal especially frustrating here is that illusionism doesn’t actually require any radical break with our most basic assumptions about the nature of conscious experience. In fact, I’m going to take a moment here to argue the opposite: That illusionism is the only approach capable of successfully preserving (and synthesizing) two of the most widespread, fundamental intuitions that lay at the heart of philosophy of mind.

That claim is obviously going to strike a lot of people as preposterous. What could be less intuitive, after all, than the idea that human cognition is built from the ground up around an impenetrable illusion that systematically misrepresents the basic features of our mental lives? But to be clear, that’s not the sort of intuition I’m talking about right now (although I promise I’ll come back to it in a bit). Rather, I’m talking about two more theoretical intuitions, whose equal and opposite force has structured the dialectic in analytic philosophy of mind for at least the last several decades.

The first of these intuitions is that the phenomenal aspect of conscious experience is, to use a technical term, really weird — that it just shouldn’t be possible for a bunch of material stuff to come together and produce the ineffable, subjective “what it’s like-ness” that comprises our view of the world. The second intuition, on the other hand, is pointing in the other direction: That there’s something deeply problematic about invoking non-physical substances or properties utterly unlike anything else in the entire universe just to plug that consciousness-sized hole. Inside a modern scientific context, where reductionist physicalist models universally beat out non-physical ones when it comes to anything outside our own heads, just throwing up your hands and doubling your ontology the moment you hit a roadblock can feel a bit like cheating.

Of course, I’m not saying everyone feels both of these intuitions equally strongly, or that everyone even feels both of them at all. And I’m not saying that these are the only considerations that determine what position someone ultimately ends up taking. But what I am saying is that, if you ask a dualist why they don’t consider physicalism a live option, the first reason they’ll usually give is that their internal, subjective sense of experience just doesn’t seem like it could possibly be reduced to boring old matter in motion; meanwhile, if you ask a physicalist why they can’t stomach dualism, they’ll probably start bringing up conservation of energy, mind-brain dependence, and all the other things that make non-physical substances or properties unacceptably spooky. So what can we do to break the impasse?

This is where illusionism comes in. See, despite being routinely dismissed as absurdly unintuitive, it’s actually the only theory out there built around affirming exactly these two commitments on their own terms. First, the illusionist will turn to the traditional, non-reductive physicalist and agree that non-physical substances or properties are an absolute dead end for any remotely respectable theory of mind — but then, before the dualist can start sulking, she’ll turn and affirm to him that yes, the ineffable redness of a rose (or whatever) really is something no collection of unconscious matter could ever actually instantiate. And that means everybody’s happy, at least until they all start to wonder just how on earth both things could be true at once.

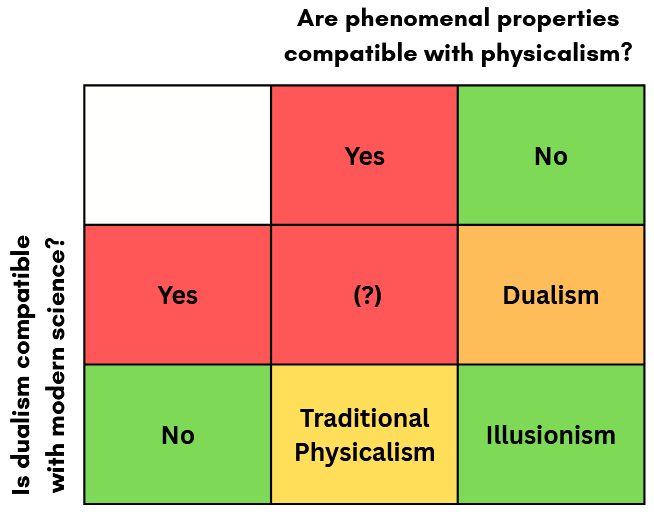

The key to reconciling these two seemingly contradictory intuitions, the illusionist says, is really pretty simple: Those phenomenal properties have features incompatible with physicalism, which is true, because those properties are (wait for it) illusory. So long as you’re willing to accept that basic claim, it’s possible to affirm the primary motivation of the non-reductive physicalist and the dualist with equal conviction, no compromise required. To help make this point clearer, I’ve even gone so far as to make a handy chart:

As you can see, the widespread intuitions are marked in green while their negations are marked in red. Dualism and traditional physicalism are both marked yellow, since they both align well with one of those intuitions while requiring proponents to reject the other. (I’m not really sure what would sit at the intersection of a “Yes” answer to both — maybe something like Michael Tye’s panprotopsychism? — so I just left that one blank.) Meanwhile, in the far corner, illusionism sits with a lovely green shade, since it can affirm both that phenomenal properties don’t play well with physicalism and that non-physicalist theories don’t play well with modern science. The result is a theory that beautifully accommodates two of the most fundamental commitments in modern philosophy of mind — hardly the absurd, out-there fantasy most of its critics make it out to be!

Another way to see this dynamic play out would be to make an analogy with an actual illusion — like, in the “magician saws a woman in half” sense — and ask what would be most satisfying explanation. So let’s say you and three friends go out one night to a show and see someone douse themselves in gasoline, burn themselves to a crisp, and then suddenly pop back to life after their assistant waves a magic wand over the pile of ash and bone. You turn, bewildered, to your three friends and ask them what the hell just happened. Here are the three responses you get:

Friend #1: “Well, obviously it’s not possible to naturally undo the effects of being burned alive, so it must be that the assistant really does have some supernatural power to bring people back from the dead.”

Friend #2: “Well, obviously the assistant can’t really have any supernatural powers, so there must be some natural way to undo the effects of being burned alive.”

Friend #3: “Well, obviously it’s not possible to naturally undo the effects of being burned alive or to have supernatural powers, so it must be that the guy on stage didn’t really burn to death at all.”

Clearly, it’s Friend #3 who’s got the situation figured out — and not only is his overall explanation better, but he’s also able to make it fit well with the intuitive judgments of the two other friends in a way that explains why they would come to the conclusions they did. As a theory of consciousness, illusionism does the same thing: In addition to providing a perfectly plausible account on its own, it also preserves and unifies the intuitions that make the other accounts so appealing. So whether you’re a dualist or a more traditional physicalist, there’s something in the illusionist framework that will directly affirm one of your core convictions and allow you to find common ground with the “opposite” side. That hardly seems like some radical, out-there theory to me!

Before I wrap up, let me circle back to the more basic, gut sense belief in the reality of qualia that I brought up at the start. Does any of this theoretical coherence even really matter if it requires rejecting the most basic assumption everyone has about the nature of consciousness? I promise I’ll tackle that question in detail when I actually write my big piece, but here’s an answer in brief: Once you recognize that illusionism actively affirms our internal sense of experience as essentially non-physical, ineffable, private, and so on, the objection really loses all its force. To be an illusionist doesn’t require rejecting anything about how consciousness seems to us — only the second-order assumption that how it seems to us is really how it is. And while sure, we might also have an intuition about that too, we should be generally cautious about rejecting any theory just because it says the world isn’t quite like it appears to us, so long as it can accommodate the appearance itself.

After all, tables and chairs certainly seem like solid objects to me, and I think I would be well within my rights to reject anyone who tells me they don’t really seem that way. But am I going to automatically reject atomic theory as a whole, just because it tells me those tables and chairs are actually 99.99% empty space? Of course not! I have no reason to expect that my intuitive sense of the world has been calibrated to accurately represent the true nature of things like that, and atomic theory itself can help explain why it is that objects look solid in the first place. Similarly, when illusionism tells us that what we take to be real, substantial phenomenality is really just a cognitive trick, we shouldn’t be any more or less surprised. What matters is whether or not a theory can explain our intuitions — demanding from the outset that it also has to affirm them as veridical is an unreasonable expectation for any domain.

As is the case with pretty much any attempt to clarify and defend illusionism, I’m sure this point won’t be enough to break through the brick wall of incredulity that keeps so many people from engaging with it sincerely. But still, for what it’s worth, that’s my pitch: If you’re out there looking for a theory in philosophy of mind that can preserve, accommodate and synthesize multiple widespread, theoretically essential intuitions about the nature of consciousness, then illusionism might be for you. Dualists can delight in the way it affirms the inherent non-physicality of phenomenal properties, and physicalists can feel confident about its refusal to accept that sort of spookiness as an actual feature of reality. So if you are in the mood for something really edgy and out-there, you might be out of luck. But if you’re looking for a conservative theory that’s got something for everyone, don’t let all the accusations of radicalism scare you off!

My impression is that the word "illusion" is essentially what causes so much trouble here. People hear "illusion" and think "trickery, fakery, delusion". And freak out. Of course, what they should think is "oh, like a stage trick performed by a magician (who doesn't actually know any magic, obviously, because magic doesn't exist)"

What is peculiar is why people continue to freak out after having this explained to them, and persistently refuse to listen to what is being explained to them. It really is weird.

I think idealism can also accommodate for the intuitions that 1) phenomenal states are irreducible to physical states and 2) there's only one kind of "thing" (i.e., monism). But idealism also has the advantage over illusionism that it also preserves a third intuition that phenomenal states are actually real.