Substance Dualists Have a Substance Use Problem

Or, why substance dualists might be really high, all the time

Substance dualists believe that the mind is immaterial. But certain physical substances, like THC or ethanol, obviously impact the way our minds function, or at least how our minds seem to function. So either these physical substances interfere with our ability to appropriately express our immaterial mental states, or else these physical substances actually distort our immaterial mental states directly. In this piece, I’m going to explain why I think both views have counterintuitive consequences for substance dualism, either because they imply we are not our immaterial minds most essentially, or because they imply we have no idea what kind of people we really are. To be clear, there are some forms of substance dualism where these conclusions wouldn’t be a problem. But for the majority of substance dualists who believe we are our immaterial minds most essentially, and that we can know what kind of people we are, the issue is a serious one.

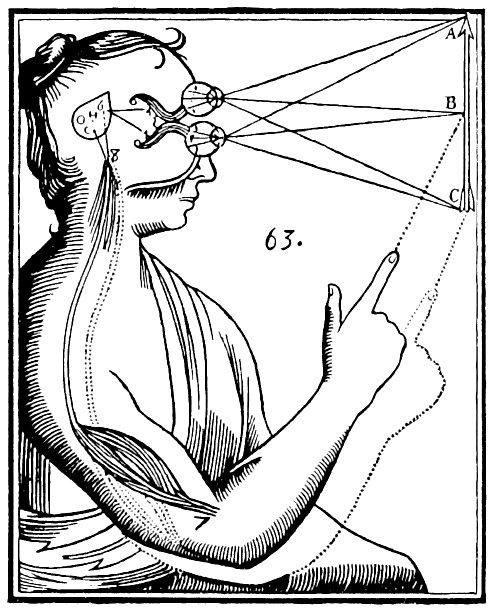

I’m going to call the first view here - that intoxicating substances don’t impact our actual mental states, but only the way those mental states are expressed - the receiver view, because people who hold this view commonly draw it out by making analogies with machines that receive and display some external signal. On this view, the physical brain is like an antenna that “picks up” the immaterial mind, and an intoxicated brain is like an antenna that’s malfunctioning in some way that distorts the signal being broadcast. I can see why this view is broadly appealing, because it helps the substance dualist preserve a sense of the immaterial mind as independent from and prior to the physical body; if you’re drawn to substance dualism because you think there’s some ineffable self you have apart from any particular physical feature, then it makes sense that you’d want that ineffable sense to be immune from physical tampering. But there are at least two major issues with the receiver view that make it significantly harder to defend than the alternative.

So what are these problems? Well, the first would be that the receiver view is wildly out of step with our actual experiences involving damaged receivers, which tend to alter relatively superficial features of the signal being received and not its fundamental character. Take an analog TV, for instance - smacking it with a hammer might scramble the colors a bit or make the audio track all wonky, but it won’t change who wins on the latest episode of Jeopardy. That’s because there are some things the signal producer is responsible for (the actual content of the broadcast) and some things the signal receiver is responsible for (how that broadcast is displayed), and interference with the receiver can only alter those features the receiver controls. But sufficiently powerful dissociative drugs don’t just distort peripheral aspects of how we internally present our mental states like a busted TV antenna might. Rather, they directly impact our mental states themselves: Our perceptions, beliefs, values, emotions, memories, rational faculties, and even our fundamental sense of a distinct, unitary self. So if the dualist accepts that intoxication can alter all possible psychological features, while also asserting that these alterations can only be the result of errors introduced after the “signal” has been sent, then they’re forced to accept that all possible psychological features are produced afterwards “on the physical side” - in which case, there’s no room in the picture left for an immaterial mind at all.

Of course, the substance dualist can object here and argue instead that the brain’s power as a “receiver” really is so great that it can dramatically alter the actual content of the pre-physical mental states originally had by our immaterial minds. To me, this is a little like someone watching a movie on their phone and thinking the main character died at the end because the wifi connection got spotty; it just doesn’t seem like problems with the receiver should be able to alter the content of the signal in such a fundamental way. But regardless, giving physical brains this sort of power brings up its own issue, which I’ll illustrate with an embarrassing personal anecdote. A few nights ago, I took a marijuana edible. (Mom, if you’re reading, I’m sorry you had to find out this way). I happened to check my work email about half an hour later and saw my boss had asked me to meet with her the next day. Immediately, I was overcome with anxiety, my THC-addled mind convincing me I was responsible for some major screw-up and surely about to get fired. But as my panic grew, I stopped to ask myself the classic stoner question: Wait a minute, is this just because I’m high? I considered the possibility for a short time before firmly deciding that no, the edible hadn’t even kicked in yet and my fears were entirely rational. And then of course a few hours later I reread it and realized I had, in fact, been very high.

I don’t share this example just to warn others about the danger of checking your work email under the influence. I also share it because, if the receiver view is true, then it gives us serious reason to doubt that we are immaterial minds most essentially, even if those immaterial minds do exist. Here’s why: At the moment in question, as I read my boss’ email, I didn’t know I was intoxicated. But assuming I have one, my immaterial mind certainly did know I was intoxicated, in the same way a broadcaster would know if the signal they were sending was being distorted. I was, after all, immediately able to understand that I was intoxicated after the fact by just reflecting on my disorganized, paranoid reasoning. But that reflection was done, presumably, with the mental powers of my immaterial mind. So if my immaterial mind never lost those powers, then my immaterial mind was aware of my intoxication at the moment I was intoxicated, even though I wasn’t. It stands to reason, then, that I am not (or at least was not, at that moment) my immaterial mind most essentially. How could I be? If some entity knows something, but I don’t, then that entity isn’t me.

This troubling divergence doesn’t just pop up in cases of extreme intoxication. It’s present whenever physical interference alters impacts our cognition in any way at all. Let’s say I skip breakfast tomorrow and end up especially grumpy in the afternoon. If it’s true that my grumpiness is the product of some particular chemical imbalance in my brain that’s altering a previously non-grumpy mental state had by my immaterial mind, then my immaterial mind can’t truly be said to have the property of grumpiness (just like a piece of music can’t truly be said to have the property of silence just because the speaker playing it cuts out for a moment). But the fact remains that I am grumpy when I skip breakfast, and something that isn’t grumpy at the exact same time can’t possibly be me. And since this sort of physical interference is going on at every moment, leading to entirely disjoint sets of pre- and post-physical mental states, then it seems like I’m always the latter and never the former; every quality I have is a quality of the “broadcast” as presented, not the signal that produced it. So on the receiver view, even if I did have an immaterial mind, it would just be a sort of mental raw material that gets turned into me, rather than what I am most essentially.

There’s nothing inherent to substance dualism that makes this conclusion necessarily unacceptable, but the vast majority of substance dualists would rather not endorse it; part of what makes substance dualism so appealing to its proponents is that the substance in question is a prime candidate for what we are most essentially. For this reason, I imagine most substance dualists would reject the receiver view in favor of a model where physical changes in the brain can and do directly impact the actual state of our immaterial minds. But this view, when combined with the belief that immaterial minds can exist apart from physical bodies, leads to another concerning conclusion: That we have no idea what kind of people we really are. After all, what kind of person you really are is determined by your most fundamental psychological features. But if someone has only ever existed in an embodied state, then they’ve only ever been aware of their fundamental psychological features as mediated by particular physical states in the brain, and we know (if we accept this view) that particular physical states can radically alter those features. So we would have no way of knowing what those fundamental psychological features would be apart from that influence, even though it’s precisely our features in that state - existing entirely as our essential immaterial self, apart from the physical body - that would truly define what kind of people we really are.

As an analogy, you can imagine a faraway planet where an indigenous plant or fungus unknowingly releases a steady stream of potent deliriants into the atmosphere. If human colonists were to land on this planet and establish an outpost, it wouldn’t be long before every person in their society was constantly experiencing paranoid delusions, hallucinations, bouts of rage, and other symptoms of severe intoxication. Assuming these colonists would be capable of surviving for more than a short period, they would eventually reach a point where no one on that planet had any idea their symptoms were unnatural; the grandchildren of the original colonists would just think that human beings really were incoherent maniacs by default. And even if those colonists did somehow stumble onto the idea that some chemical in the atmosphere was responsible for radically distorting their psychological states, they couldn’t know how it was distorting them without a human from earth to act as a control. For all they know, that sort of human is even more delirious and frenzied, and the unknown chemical on their planet has a calming effect! With only their own mental states and the fact that some distortion is occurring, they simply don’t have the information necessary to know what “default humans” are really like.

This, I argue, is the situation all human beings would find themselves in if the sort of substance dualism mentioned above were true. Our essential selves as they exist apart from a physical body would be like the humans back on earth, free from any disfiguring influences, while we would be stuck as the colonists struggling to imagine what they’re like. Maybe the immaterial mind that I am most essentially has a default nature of pure joy and moral goodness, dragged down by the fetters of the physical world - or maybe that mind is so vicious and cruel that natural selection favored a brain capable of curbing its most destructive impulses. I’d simply have no way of knowing! So long as I have no contact with disembodied minds and the sorts of features they display, I’m incapable of determining the degree to which any chemical in my brain - from the occasional dose of THC to the omnipresent drip of dopamine or serotonin - distorts those features from their pre-physical baseline. Just like a permanently intoxicated person could only ever guess at the nature of sobriety, a permanently embodied person could only ever guess at the nature of their unembodied self.

This conclusion isn’t necessarily unwelcome for some substance dualists. In fact, it aligns well with traditional Hindu perspectives on the relationship between particular beings and their eternal Ātman, or even some reformed Christian speculation on the noetic effects of the flesh. But unless you already have confidence in the spiritual practices these traditions rely on for insight into the essential self’s properties, it should still be very concerning to think that the nature of your true self is completely opaque. (And I think there are good reasons you should not have that kind of confidence.) Reductive naturalism, on the other hand, has no comparable issue - while it still might be the case that our cognition misrepresents the actual world in some way, someone who holds that mental states just are physical states never needs to worry about the nonsensical question of what the former would be like apart from the latter. This isn’t a decisive point in reductive naturalism’s favor, but it is a substantial advantage of the theory, and it should push substance dualists to consider whether their embrace of an immaterial mind really gets them everything they’re looking for.

Interesting read!

I think there is at least one easy way for the substance dualist to get out here, which is to just be an epiphenominalist. On this view, there's nothing strange to be explained. It does of course also mean that there is no "real way you are" apart from your brain, but I don't think that's particularly strange either.